À l’ouest de la Normandie, vers 1650, les seigneurs de Balleroy fondent un nouveau village aux marges d’une forêt royale… Nous vous invitons à découvrir l’histoire de ce petit bourg rural à l’urbanisme particulier grâce à notre exposition en 8 tableaux.

In western Normandy, around 1650, the Lords of Balleroy founded a new village on the fringes of a royal forest… We invite you to discover the history of this small rural village, with its distinctive town planning, in our 8-panel exhibition.

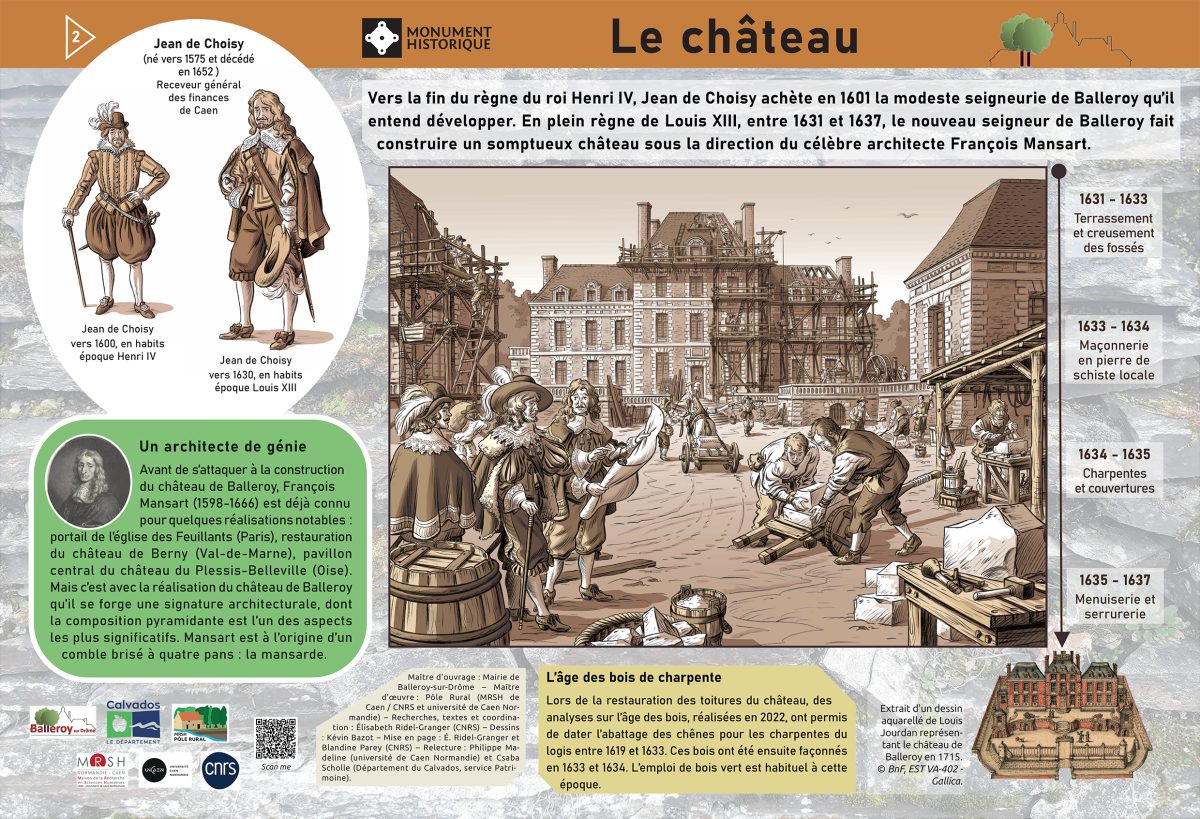

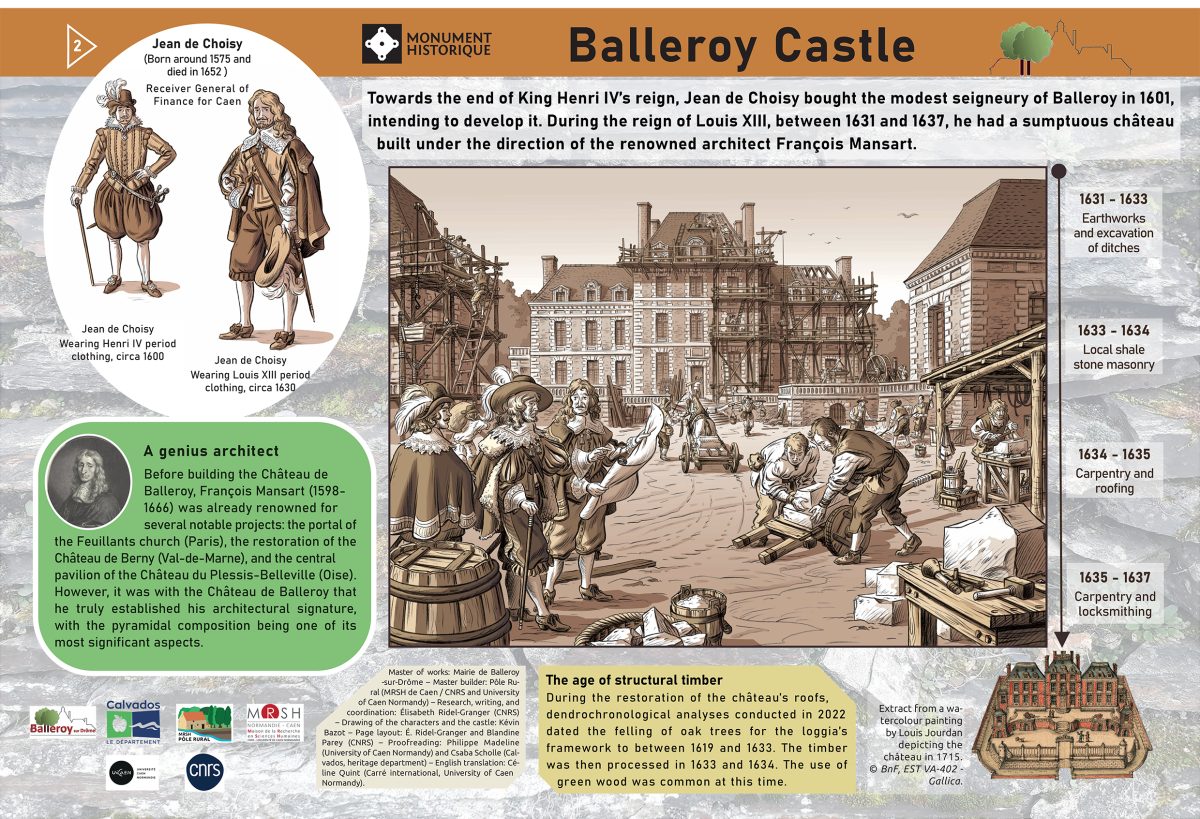

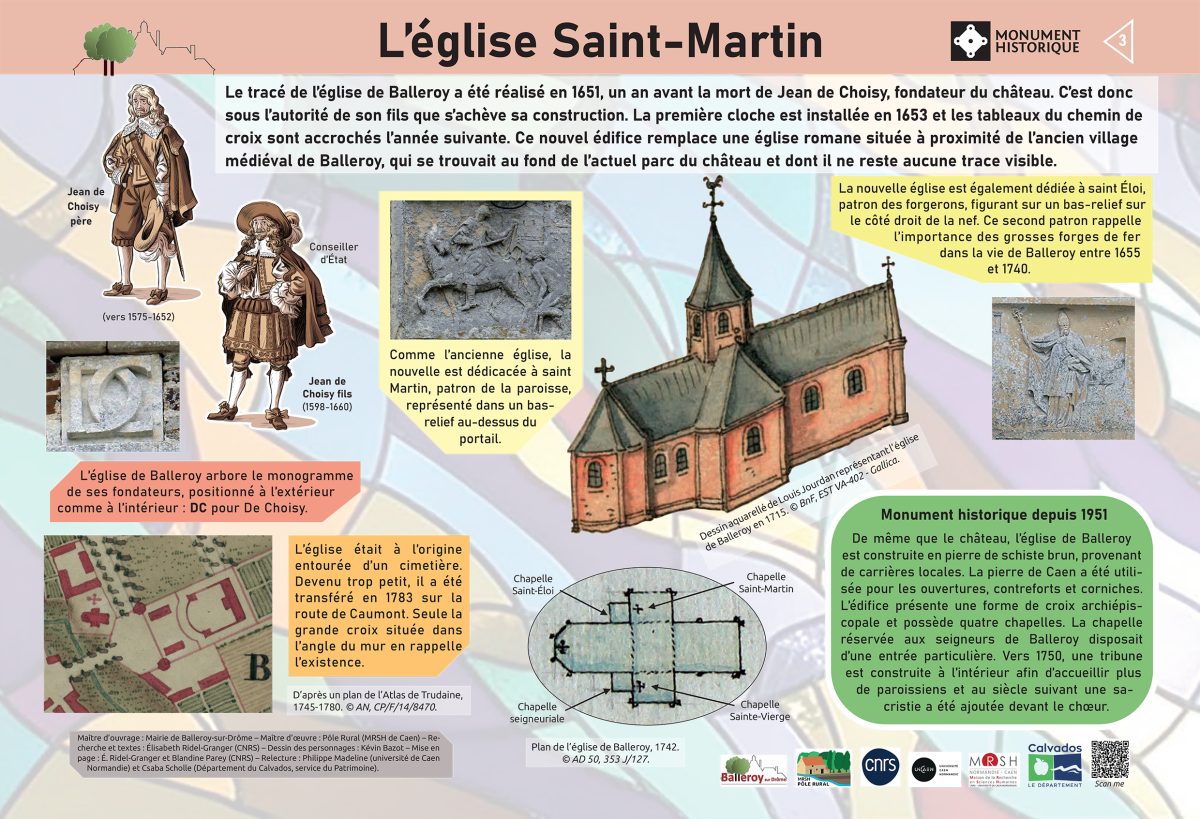

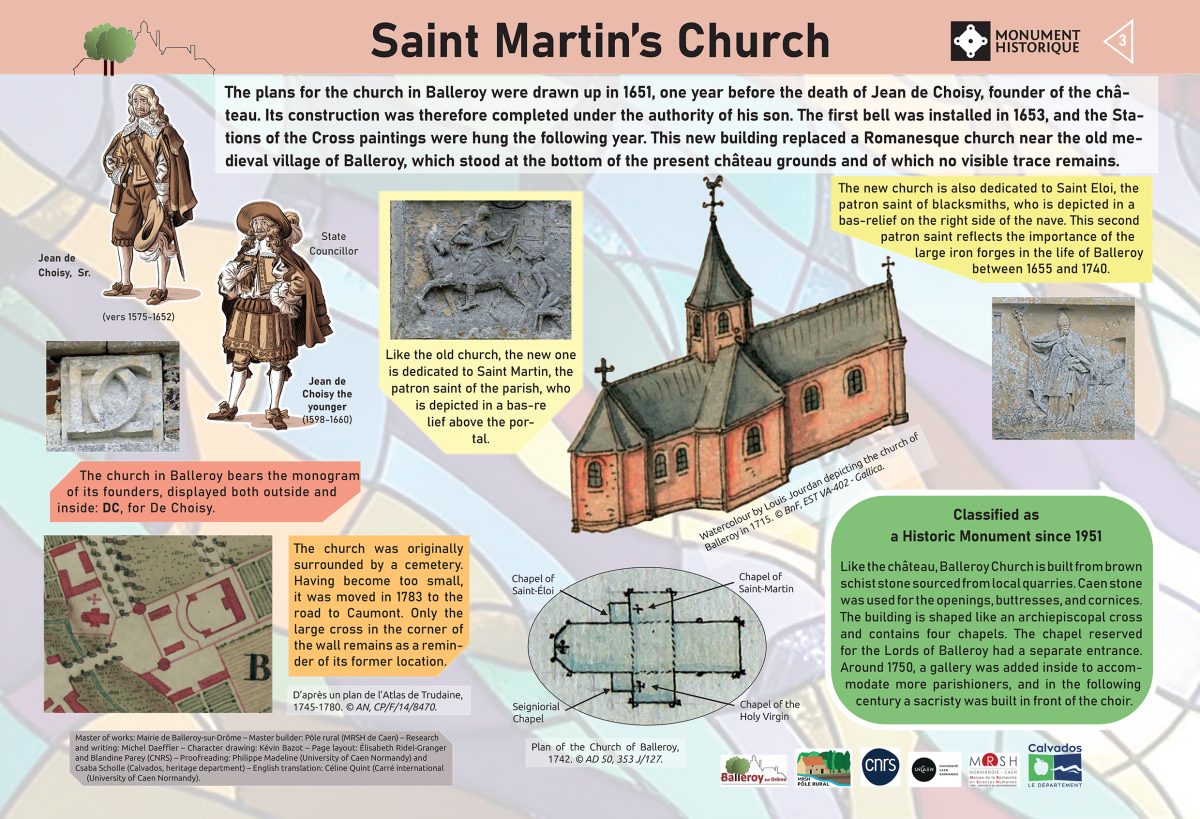

Alors que le maillage des villes est déjà bien défini en France à la fin du Moyen Âge, la période moderne connaît la mise en chantier de villes neuves, créées de toutes pièces à proximité de villes anciennes. Ces créations sont rares : on compte moins d’une cinquantaine de villes neuves qui ont vu le jour entre le XVIe et le XVIIIe siècle. Si ces créations se sont souvent appuyées sur des conditions démographiques, géographiques et politiques préexistantes, elles se sont en général établies sur des terrains vierges d’habitations, permettant ainsi le développement d’idées nouvelles d’urbanisme. À l’instar des villes de Richelieu et de Versailles, le bourg de Balleroy fait partie de ces projets urbains novateurs, à la géométrie audacieuse et à l’esthétique harmonieuse. En effet, bien qu’il ait existé un village médiéval à Balleroy, dont les archives du XIIe siècle se font l’écho, le bourg que nous voyons aujourd’hui n’en est pas l’évolution. Édifié au cours de la seconde moitié du XVIIe siècle dans le prolongement d’un château de style Louis XIII, il est l’émanation d’un projet d’urbanisme original conçu par Jean de Choisy père et fils, seigneurs des lieux, et le célèbre architecte François Mansart, bâtisseur du château.

While the network of towns was already well established in France by the end of the Middle Ages, the modern period saw the construction of new towns built from scratch near older ones. These creations are rare: fewer than fifty new towns were established between the 16th and 18th centuries. Although they were often based on pre-existing demographic, geographical, and political conditions, they were generally founded on land that had never been inhabited before, thus allowing for the development of new urban planning ideas. Like the towns of Richelieu and Versailles, the village of Balleroy is one such innovative urban project, characterised by its bold geometry and harmonious aesthetics. Although a medieval village in Balleroy is mentioned in 12th-century archives, the town we see today is not an evolution of that earlier settlement. Built during the second half of the 17th century as an extension of a Louis XIII-style château, it is the result of an original urban planning project designed by Jean de Choisy, father and son, lords of the manor, together with the famous architect François Mansart, builder of the château.

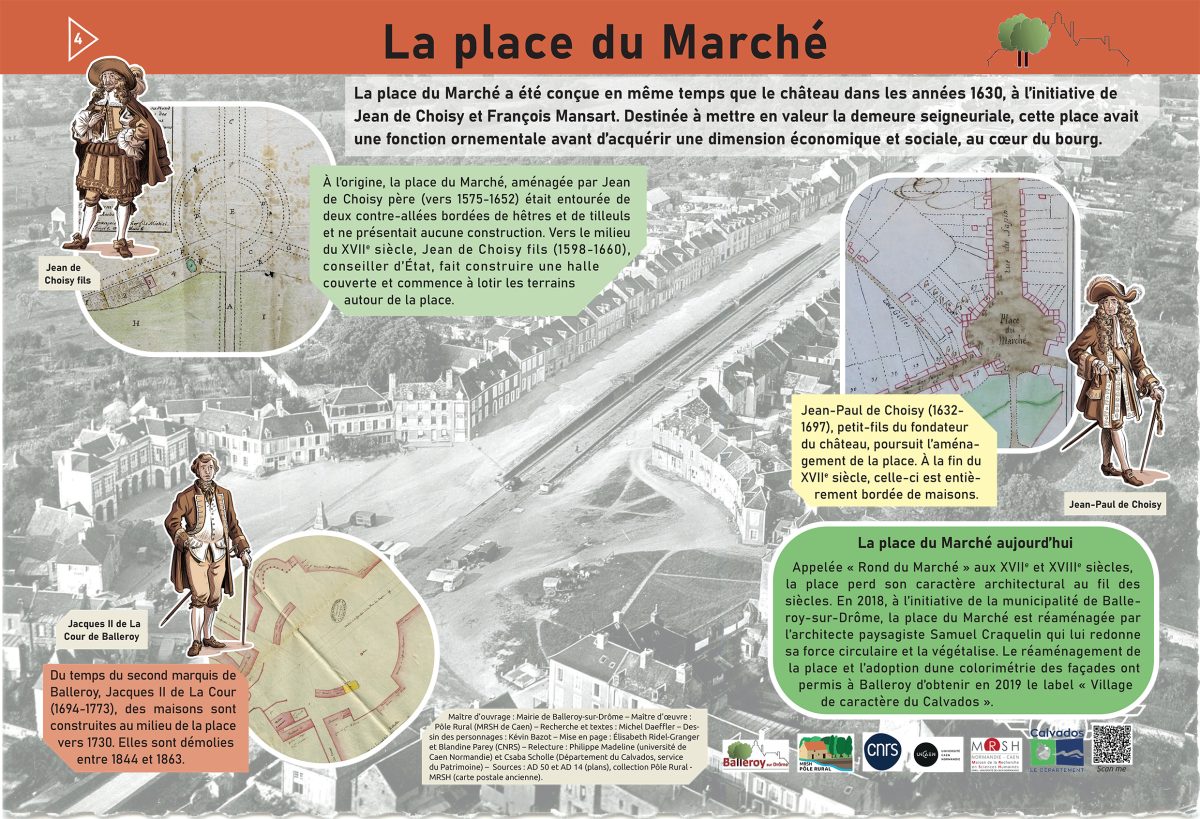

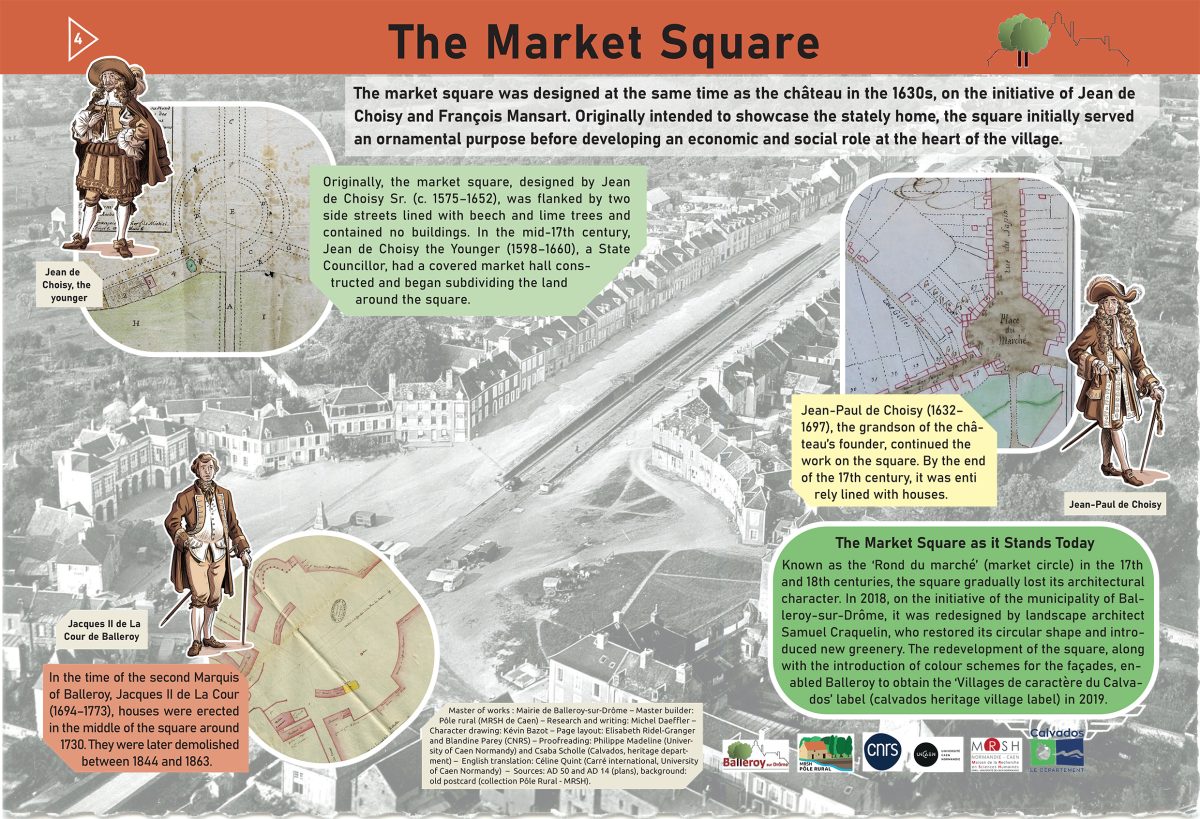

Aujourd’hui, encore, le bourg de Balleroy (Calvados) dénote dans le paysage rural par son plan d’urbanisme audacieux qui met en valeur de manière spectaculaire la demeure seigneuriale. Ce plan est fondé sur trois éléments architecturaux remarquables : un château construit entre 1631 et 1637, une grande place circulaire – démesurée pour la taille du village –, et un réseau viaire organisé autour de la place et constitué de trois rues principales rectilignes formant une patte d’oie. La marque identitaire des seigneurs a été jusqu’à s’imprimer dans l’aménagement des maisons individuelles qui ont été construites selon un alignement précis imposé par les maîtres des lieux.

Even today, the village of Balleroy (Calvados) stands out in the rural landscape for its bold town-planning scheme, which spectacularly highlights the manor house. This plan is defined by three remarkable architectural features: a château built between 1631 and 1637, a large circular square – disproportionate to the size of the village – and a road network organised around the square, consisting of three straight main streets forming a crow’s foot pattern. The identity of the lords was even reflected in the layout of the individual houses, which were built in strict alignment, as dictated by the masters of estate.

Outre le château et l’urbanisme particulier du bourg, l’empreinte seigneuriale s’est également affirmée dans l’espace bâti par la présence d’édifices représentatifs du pouvoir : l’église et les juridictions, les forges et le manoir du maître des forges, les halles et les moulins banaux.

In addition to the château and the town’s distinctive urban layout, the seigniorial imprint was also evident in the built-up area through the presence of buildings representing power: the church and the courts, the forges and the forge master’s manor, the market halls, and the communal mills.

Sur le plan patrimonial, le réaménagement de la place du Marché en 2018 et la mise en place d’une colorimétrie ont permis à Balleroy de recevoir en 2019 le label « Village de caractère du Calvados ».

In terms of heritage, the redevelopment of the Place du Marché in 2018 and the introduction of a colour scheme enabled Balleroy to be awarded the « Village de caractère du Calvados » label in 2019 (a designation awarded to villages recognised for their architectural, historical, and cultural heritage).

Élisabeth Ridel-Granger, CNRS – MRSH, codirectrice du Pôle Rural

Translation Céline Quint, Carré international – Université de Caen Normandie