Death Records: An Endless Documentary Trail

As men of letters and social relations, well integrated in the rural environment and given a mission as public officers by the state, priests acted as informers, providing detailed accounts within their official writings. This was the case for death records, which (in France) they had to keep from the 16th century onwards, with regulation by the local authorities from 1667. After priests, it was mayors who took over civil records, without detailing the tragic circumstances of accidental deaths caused by wolves. However, some records give accounts of attacks until the start of the 19th century.

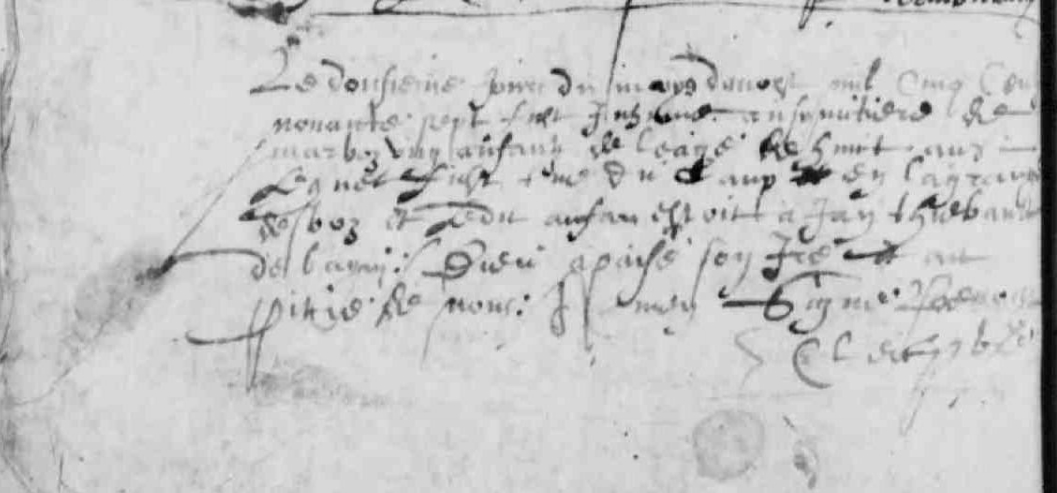

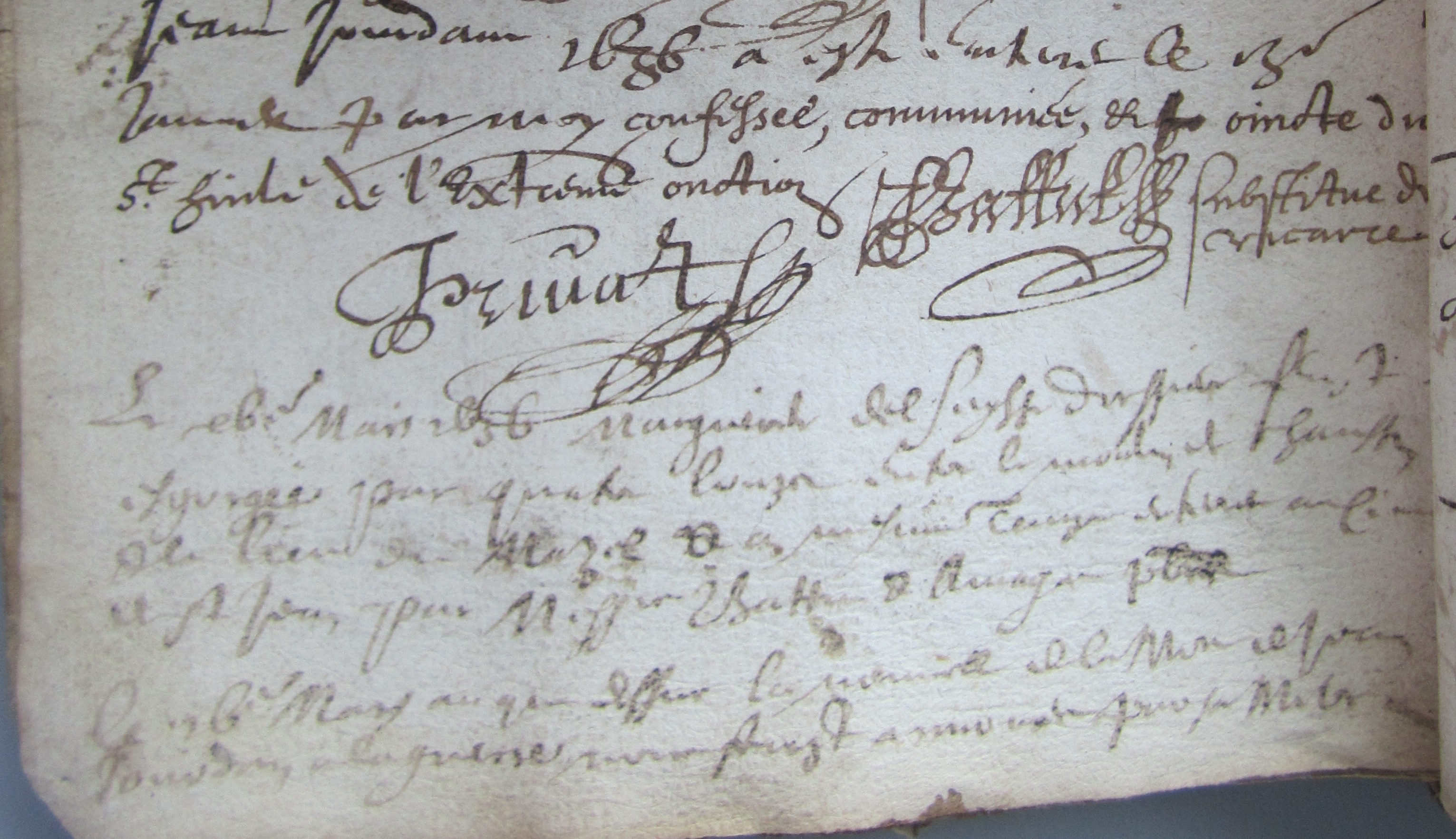

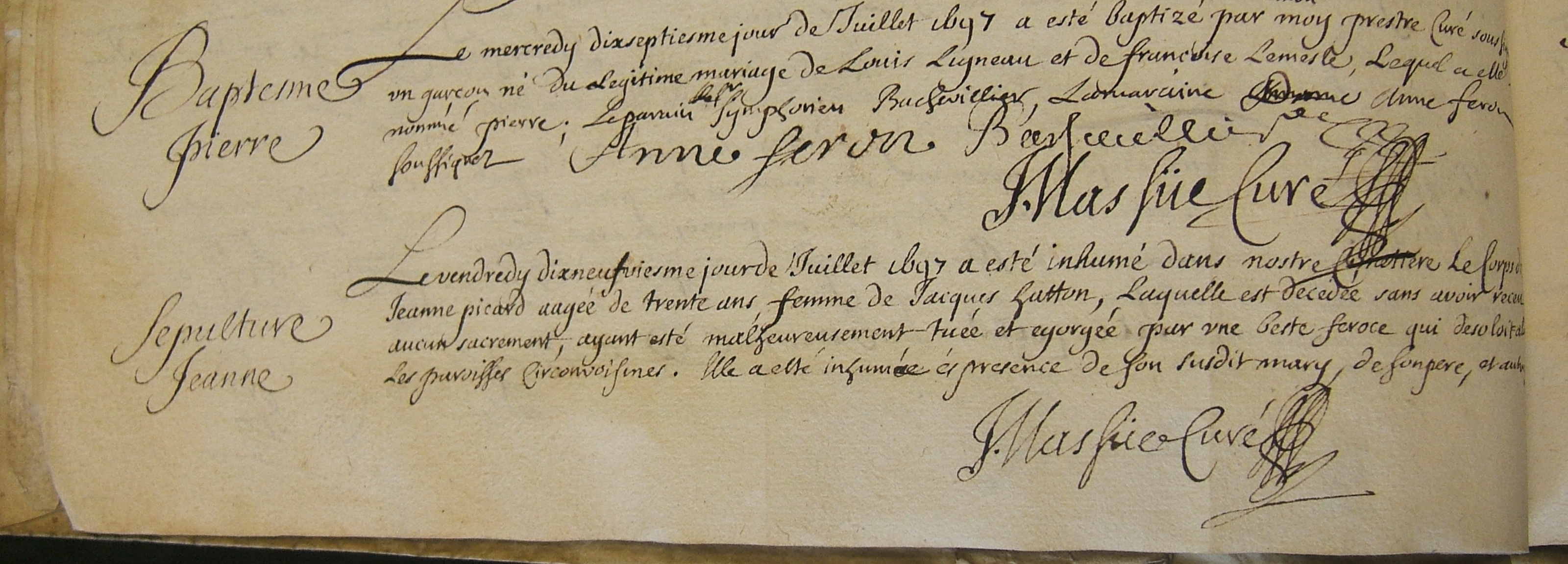

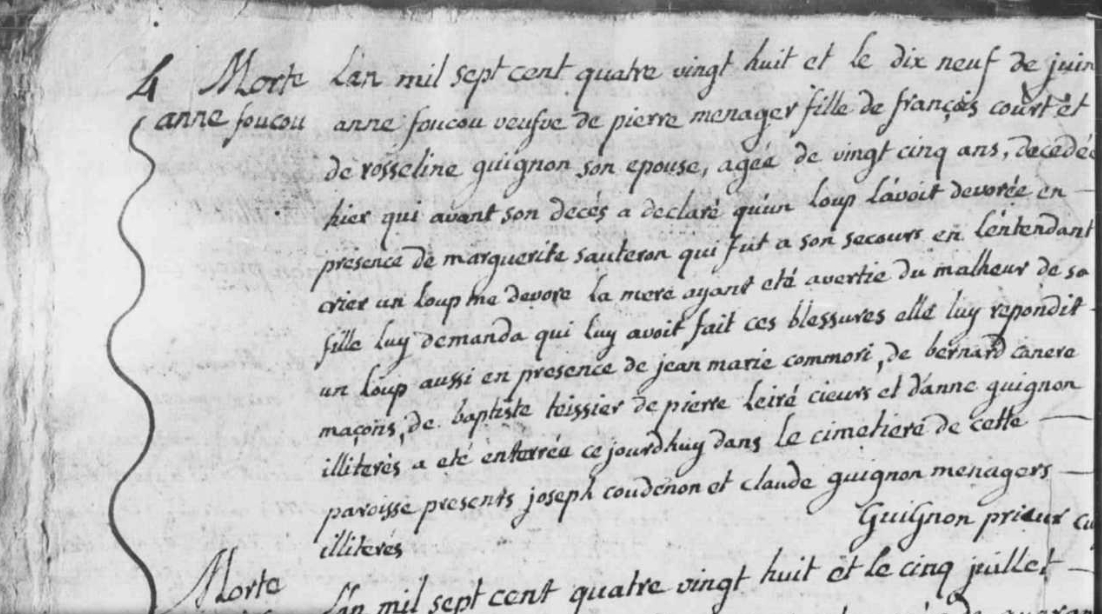

Burial records contain thousands of useful mentions for our purposes, from the recording of deaths at the end of the 16th century until the secularisation of the civil state in 1792. Consequently, as administrators of the sacraments, parish priests often explained why they were giving Christian burials to people who had not had a chance to make penance, or receive the communion or the Extreme Unction. The anthropological transgression of wolves attacking humans, which was worse when the victim was found partially eaten, and the emotion surrounding the dramatic circumstances of death, motivated some priests to write. Wolf attacks left victims mutilated or dismembered. Records sometimes contain comparable explanations for murders and deadly accidents, but wolf attacks were even more frequently recorded in registers.

For rabid wolves, the variability of the period between the attack and death from rabies, and the particularly high geographical mobility of the victims, who tended to leave their parish to seek care elsewhere, make sources less useful: these victims do not appear where expected. However, for predatory wolves, the quick death meant that attacks were recorded on site. With the odd unavoidable exception (complete disappearance of bodies, few remains, unrecorded incidents), burial records were written for most attacks.

How useful are these sources? How far can we trust those who wrote them? The validity of this database greatly depends on the answers to these questions. Register-keepers were well-placed to inform. Under the Ancien Régime, the civil status and social position of rural priests was nothing like that of their current counterparts. They were valuable administrative auxiliaries, and they kept neutral and authentic records which were used by the legal system to identify victims and perpetrators. They knew their environment well, and were often agricultural landlords, farmers, livestock farmers, or game hunters. As eyewitnesses, they were often familiar with wild animals. As well as being rigorous in their duties, they were good observers, even providing details on the circumstances of attacks, or acknowledging a degree of uncertainty. The temporal and geographical consistency of their accounts (excluding differences due to the personality of those writing and the particularities of regions and periods) makes them a more reliable source for historians. With the vicars who assisted them, they formed a network of almost 100,000 informers spread across the whole territory.

The only real limitation of this category of sources is under-recording. The records were affected by changing regulations, which were increasingly demanding from 1667, meaning that information is better for later years. After 1737, it is excellent, even if there are still gaps, due to the loss of certain registers, or the omissions or concision of those who kept them. In fact, those who kept parish registers were not bound to give these indications systematically. Although the vast majority of them did, certain incidents still slipped through the net. Moreover, witnesses were required, to authenticate the records and (if they could) to sign them. These procedures mean that we have no reason to doubt the reliability of the records.

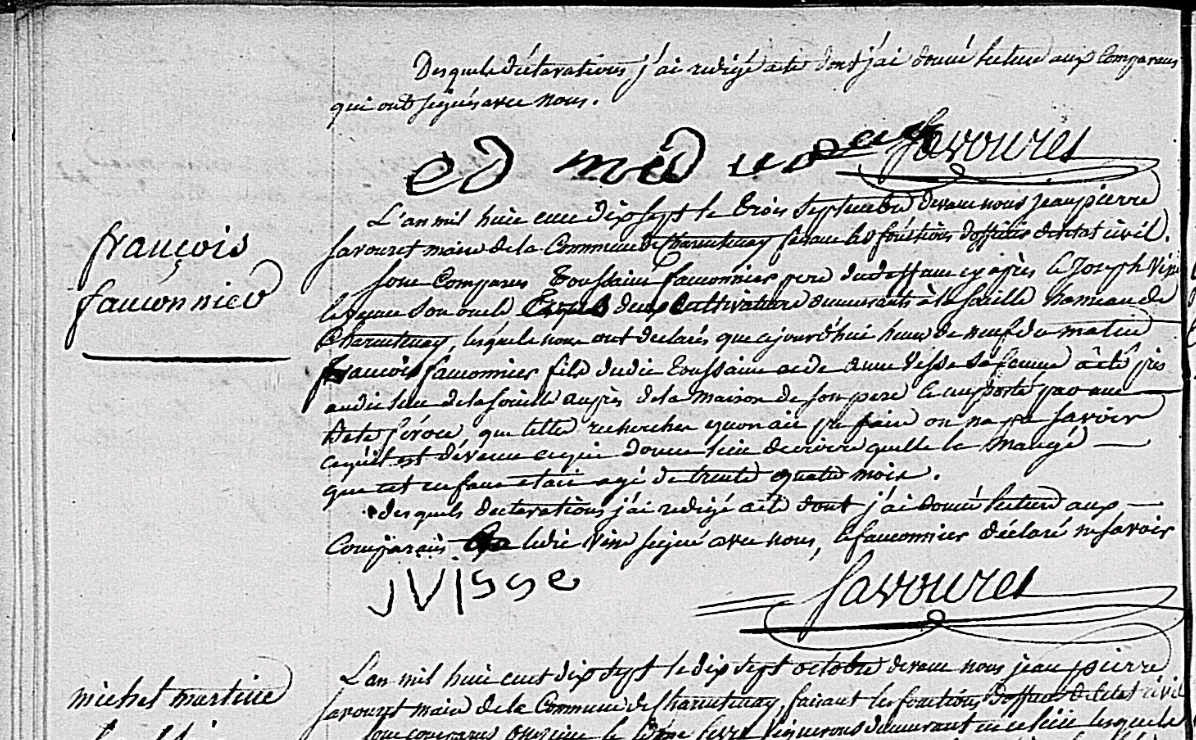

In the 19th century, civil records took over, and their reliability depended on the precision of mayors. Some mention the causes for a few tragic disappearances, for example the Gravières records, in which the death of Marie Chat, of the village of Albourniès, was reported as follows: “A three-year-old child, deceased at 11 AM, near to her house, devoured by the wolf” on 28 October 1812. Up to the last attacks attributable to occasional man-eating wolves, civil death records (which had even less reason than parish registers to explain these brutal deaths) provide documentary evidence.

Death records provide a qualitative contribution, which even goes as far as providing a real report on the identification of the body, and in certain cases, as far as describing the animal which attacked in the margin of the register, with some writers even sketching the wolf. Moreover, the frequency of the information is useful for quantitative study, as it provides a corpus that is suitable for statistical analysis.