Administrative Sources:

Accounting or Statistical Sources

Intendants’ Correspondence

Tax Documents and Administrative Rewards

Notes and References

Accounting or Statistical Sources

A further category of sources comes from the activities of the public authority responsible for protecting populations and compensating victims. From the Middle Ages onwards, these accounting sources corroborate the statements in narrative sources. In 1378, the “scrolls” of the house of the Duke of Burgundy, feature “a poor man whose arm had been eaten by wolves”. In the same year, on the name Jacotte de Fouvant, a townswoman who had disappeared without a trace, the Dijon “household search” says that: “nobody knows what became of her, and it is said that the wolves ate her”.1 At the start of the reign of Louis XI, officers of the Chamber of Accounts drew attention to the wolf attacks around Melun: in the 1460s, in the space of six months, wolves are supposed to have throttled and eaten 19 people, and injured more besides. The officers of the Chamber of Accounts therefore alerted the king, because of similar complaints from elsewhere.2

Intendants’ Correspondence

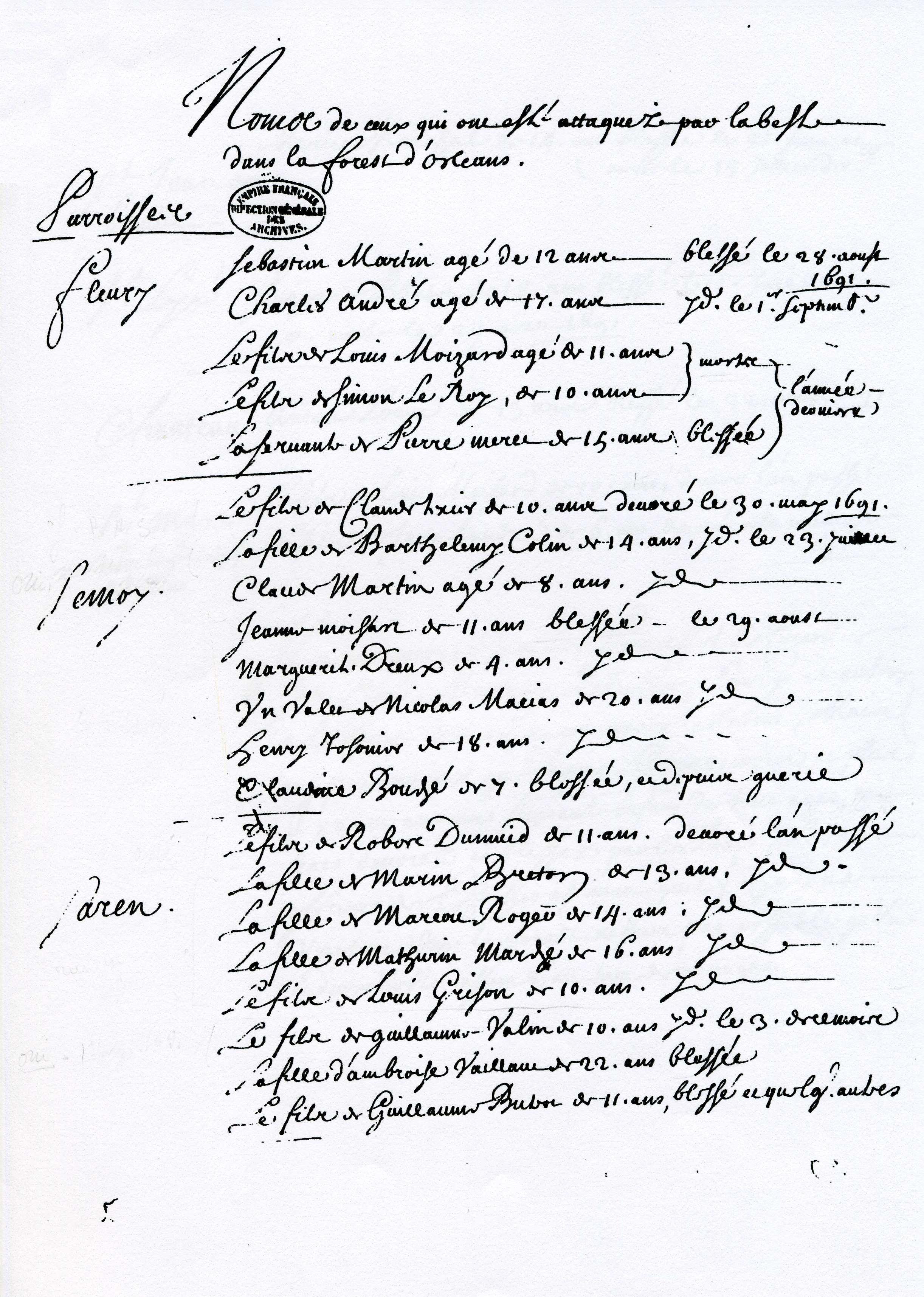

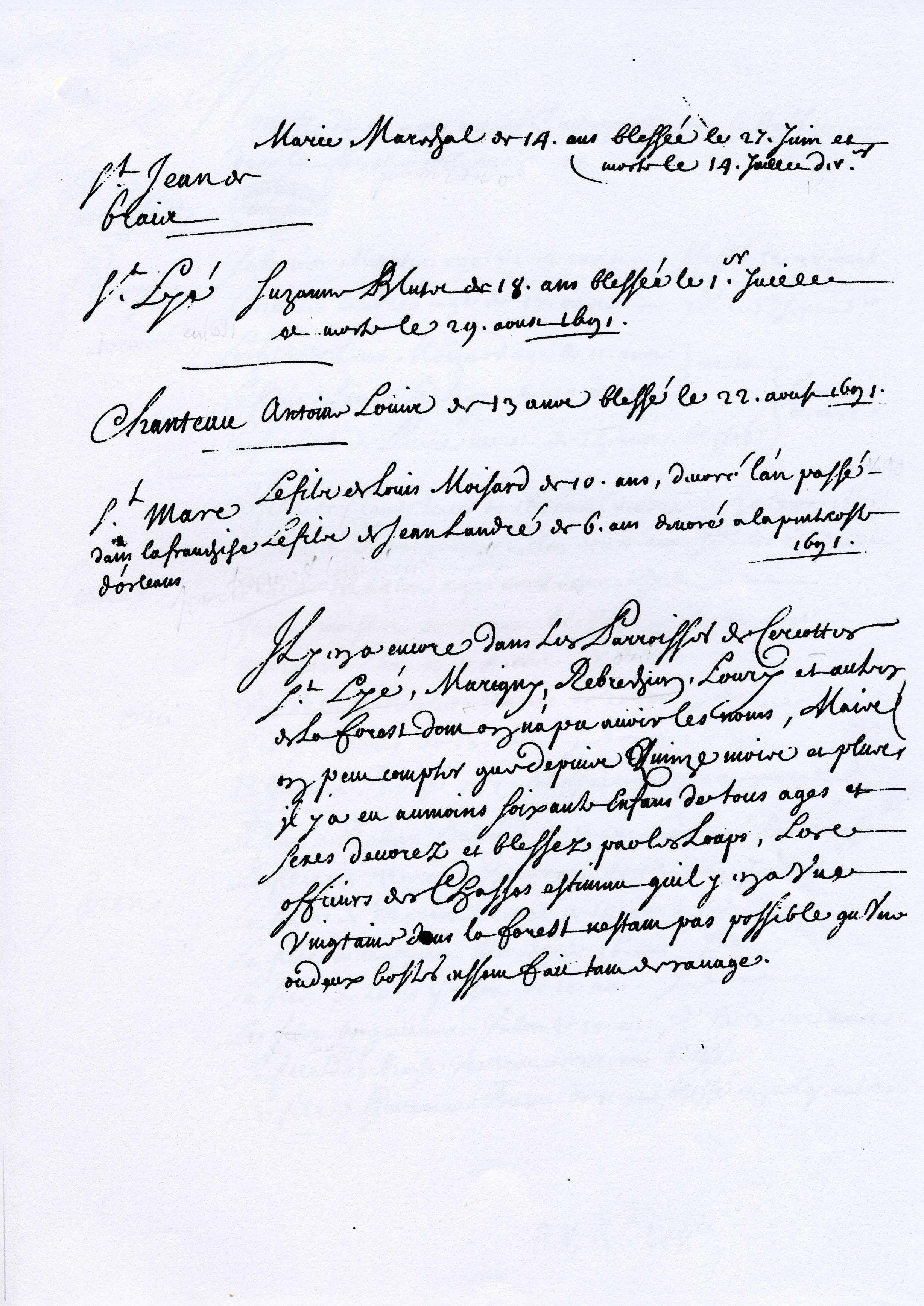

The institution of provincial intendants during the 17th century shows a real, unprecedented effort to inform and control. It led to growing administrative correspondence with higher authorities (the Chancellor, then the General Controller of Finances, and other royal ministers) and lower agents (sub-delegates, various officers, parish priests, etc). The severe threats to public safety prompted investigations. The spates of attacks attributed to man-eating animals were documented with increasing precision from the reign of Louis XIV onwards. Intendants’ correspondence, only some of which is published, provides an intermediary perspective between the subjective accounts of local witnesses providing the narrative sources (of which we have already established the usefulness) and the more general documentation, such as royal orders and hunting agreements. These administrative archives sometimes allow us to assess the discrepancy between the events and the reactions that they provoked. The administrative documentation includes local and regional surveys, which developed from the reign of Louis XIV onwards. Intendants’ correspondence and reports, such as that of the Generality of Orléans in 1961, sometimes make victims countable.

This is a valuable resource, because it reveals the high number of people only injured: a statistic which often escapes historians. A generation later, in 1765, it was copious administrative correspondence, particularly that of the sub-delegate Laffont, which documented the Beast of Gévaudan affair. From one province to the next, these writings make it possible to situate waves of attacks. These episodes continued after the Revolution. The last spate of attacks recorded in France, in Nivernais and the south of Gévaudan in the second decade of the 19th century, is abundantly described in correspondence between the mayors, prefects, and sub-prefects concerned.

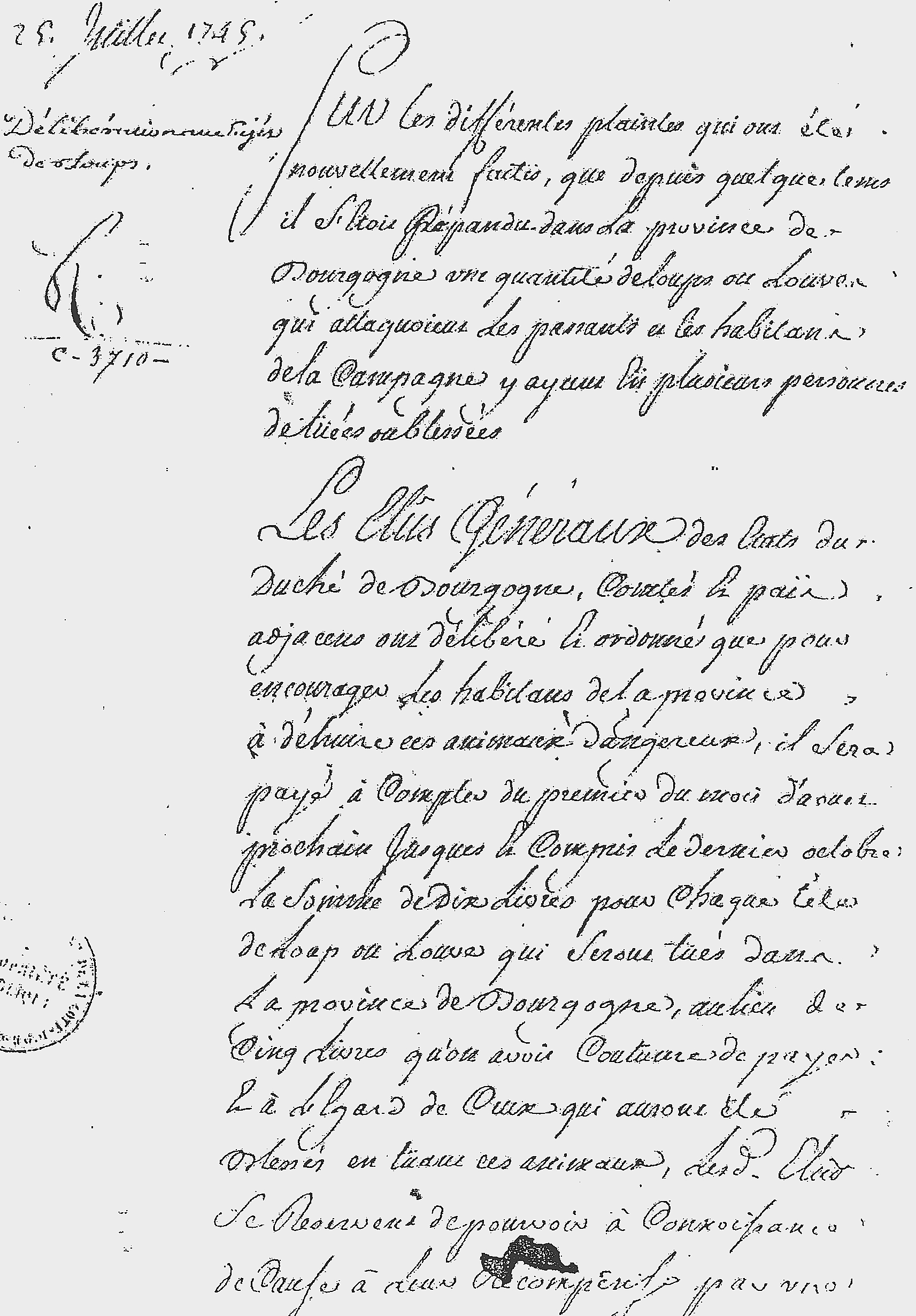

Tax Documents and Administrative Rewards

In the administrative sources, tax documents record wolf attacks when taxpayers’ livestock, or even the taxpayers themselves, suffered a deadly bite. On-site investigations resulted in tax reductions.

Rewards for killing wolves were also scrupulously recorded in accounts. These rewards provide an old source going back to the Middle Ages and continuing until the 19th century. They offer useful clues about the relationships between men and wolves, because they varied between regions and periods, and according to the level of danger. In periods of severe threat to humans, rewards might be higher. However, this regulation of attackers was only occasionally motivated by attacks on humans. It was primarily used to reduce damage to livestock. The wolf threat glimpsed through rewards must therefore be taken more widely. The information it provides is also more plentiful because each year, there were rewards for thousands of animals killed. These rewards therefore provide an indicative map of wolf distribution, first regional, then national from 1789. In this respect, the Jacobin standardisation and centralisation are very helpful to researchers. It is thanks to departmental statistics from the year V of the French Republican calendar (1796-1797) to the year IX (1800-1801) that it has been possible to create the first national maps of wolf distribution over the territory.

Notes and References

- 1 Étienne Picard, « La vénerie et la fauconnerie des ducs de Bourgogne », Mémoires de la société éduenne, t. ix, 1880, p. 367 ; Jean Richard, « Les loups et la communauté villageoise. Quelques documents », Annales de Bourgogne, t. xxi, 1949, p. 285 ; Arch. dép. Côte-d'Or, B 11574-2, f° 6v° d'après Corinne Beck.

- 2 Bibliothèque de l'École des chartes, 1885, p. 295, n° 1210.