Posters, Periodicals, and Newspapers: A Distorted Reflection?

The impact of certain incidents often extended beyond just local memory. For waves of killings attributed to the great Beasts (which we will look at later), the printed media seized upon certain affairs. The imagery employed made widespread use of “figures” designed to shock the public. In 1587, a Trojan printer, Michel Buffet, published the “figure of a man-snatching wolf found in the Ardennes forest” to accompany an account of the animal’s attacks in several towns and villages in the area. The face shown for the animal, part-way between a tiger and a wolf, reflected it monstrous nature. In 1653, at the time of the attacks by the “horrible monster” that spread terror in Gâtinais, Nicolas Bery, a Parisian printer, used a similar image, making it even more hybrid, and adding a sprawling tail and long teats. The beast’s agility and speed are expressed in a rangy morphology, showing that in the eyes of the witnesses asked to identify it, in a report printed behind the image, it was somewhere between wolf and greyhound. The animal behind, however, is much closer to the flesh-hungry wolf. This type of representation was common in the 17th century, and it peaked from 1764 to 1767 with the Beast of Gévaudan. Until the 19th century, popular imagery still used this type of depictions, illustrating the drama of 6 December 1814, which occurred in communities around the Forest of Orléans.

Targeting the general public, and sold in bookshops and paper shops, or transmitted via the campaigns of hawkers, these images helped to feed the negative view of wolves. By attempting to create media hype around sensational events, they gave accounts of tragedy a geographical and temporal resonance, which must be placed in perspective today. The way in which wolves are represented focuses on the “abnormal” nature of their behaviour and the morphology of the attacking animal, with a sort of transgression of the natural order. They are part of an iconographic tradition, the characteristics of which become clear when a large corpus is appropriately analysed. Despite being exaggerated, these images nevertheless provided clues that point us towards other sources.

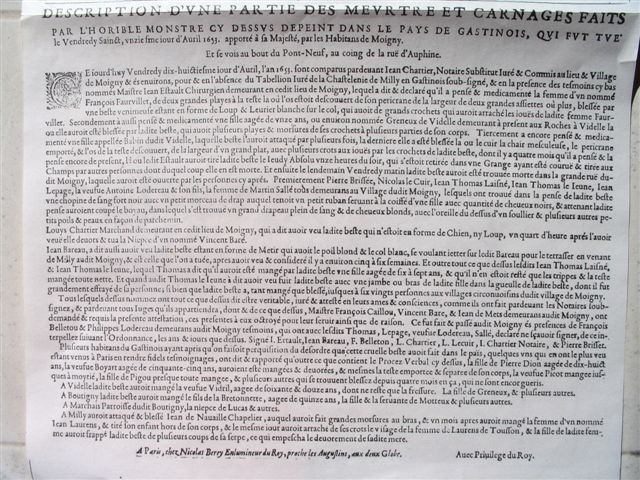

This advantage immediately becomes clear when the images accompany accounts, often in the form of reports. In 1653, the figure of the Beast of Gâtinais marked Parisian minds with the memory of the horrible monster killed on Good Friday and brought before the young Louis XIV by the people of Moigny. At the end of Pont-Neuf, on the corner of Rue Dauphine, the poster gave the “description of some of the murders and carnages” carried out by the terrible animal. In order to give the greatest possible authenticity to the event, the text cited the notarised report, which formally listed all of its crimes. Over a century before the public document which made the extermination of the last beast of Gévaudan official in 1767, the Moigny-sur-École notary’s minutes recorded the “historical” truth, by registering the witnesses who saw the surgeon carry out the autopsy on the animal, and reporting on the care administered to the non-fatally injured victims.